©2014, Aaron Elson

As a gangly teenager in Stockbridge, Mass., Ed Forrest, with his blond hair and wire rim glasses, was a cowlick short of climbing off a soda fountain stool and stepping off the cover of the Saturday Evening Post.

Edmund Laine was the minister at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Stockbridge, across the street from the historic Red Lion Inn. A portly, charismatic preacher, he was an expert in Shakespeare, and was active in the town’s affairs.

Ed worked for Reverend Laine after school, doing odd jobs around the church and parish hall. His mother died when he was 14, and a few months later Ed moved into the rectory following a fight with his alcoholic father. The minister proceeded to raise him like a son.

Laine was a chaplain in World War I, and still suffered the

aftereffects of being gassed, including frequent fevers and bouts of

dizziness. Still, he relished taking out his postcards and memorabilia

and telling stories about the Great War to Ed and his friend Dave

Braman and the other boys who played pool and hung out in the parish

hall .

.

In 1929, when Ed was 19, Laine gave Ed a small, hardbound copy of “England to America,” a short story by Margaret Prescott Montague that originally appeared in the Atlantic Monthly and was the winner of the first O. Henry Prize. It was the story of a dashing young lieutenant from Virginia who joins the Royal Air Force in World War I. He finds himself with two weeks’ leave, and his captain insists that he go visit the captain’s family. The lieutenant spends a few days in London, then visits the family in the countryside.

Despite the fact that he tells the captain’s parents he would follow their son “into hell and out the other side,” the parents treat him awkwardly, the father often turning away at the mention of his son. The lieutenant speculates that this awkwardness is due to the cultural differences between the English and Americans – hence the title – and figures he must be saying the wrong thing. In actuality it is because the captain was killed in a dogfight the day after the lieutenant left, and the family is doing everything they can to shield him from learning of their son’s death, because they knew how precious it is to have time away from the front.

Like the young man in the story, Ed wanted to be an officer, but he was colorblind. After being turned away from Officers Candidate School, he had his friend Dave help him memorize the colorblind test, and took it again.

Ed “was real conscientious,” recalled Lieutenant Bob Hagerty, who was a sergeant in Forrest’s platoon in the 712th Tank Battalion before receiving a battlefield commission. “He wore wire rim glasses, and was so thin his adam’s apple would bob up and down, and was real clear in the contour of his neck. He looked totally out of place with a steel helmet on. He wouldn’t strike fear in you if you looked at him, but he really wanted to do his job and do it well.”

The 712th was a so-called “bastard” battalion, an independent unit with no division affiliation, although once in combat it was attached almost exclusively to the 90th “Texas-Oklahoma” Infantry Division. At full strength the battalion had 765 men and 67 tanks. Ed Forrest commanded the five tanks and 25 men, plus a handful of maintenance personnel, of A Company’s third platoon.

The battalion landed in Normandy three weeks after D-Day, and entered combat on July 3, 1944.

In his first week of combat, two of Ed’s sergeants became casualties. His platoon sergeant, Charles Fowler, who at Fort Benning was a spit-and-polish, by-the-book, barrel chested noncom, had to be relieved due to battle fatigue after stuffing a tree branch into the barrel of his tank’s 75-millimeter cannon and insisting the tank was out of commission; and a hatch cover jiggled loose and slammed down on Hagerty’s fingers, an all-too common injury among tank commanders in the uneven Normandy terrain.

One morning during that first week of combat, Ed’s company commander, Capt. Clifford Merrill, called him aside and asked if he would volunteer for a particularly dangerous mission.

There are two versions of what that mission was. The way Merrill recalled it, he wanted to “stir things up,” so he put Ed in contact with a spotter plane and sent three of his tanks into enemy territory with no infantry support. The way Neal Vaughn, a gunner in Ed’s platoon, remembered it, the company was temporarily assigned to the newly committed 8th Infantry Division which had lost contact with one of its companies and asked for some tanks to go and look for them.

Either way, Forrest and the three tanks in the first section of his platoon penetrated three miles behind the German lines, didn’t find any lost infantry company, and had to shoot their way back.

“Buddy we was comin’ to hell,” is the way Ed’s driver, George Bussell, recalled the mission. At one point they turned a corner and Bussell saw three German motorcycles parked outside a building. “We ran over them,” he said matter-of-factly. Earlier, Bussell sabotaged the governor on his 33-ton Sherman tank by driving it up against the trunk of a large tree and gunning the engine until the tank practically began climbing the tree. He claimed it could outrun a jeep. During the foray behind enemy lines the tank sustained some damage to its suspension system, but all three tanks made it back safely, knocking out a small and a medium German tank along the way. Ed was awarded the Silver Star.

Two weeks later, Ed and his platoon sergeant, Reuben Goldstein, were caught outside their tanks during an artillery or mortar barrage and took shelter at the base of a hedgerow.

“The safest place is under the tank,” Goldstein said, “but Ed couldn’t get back fast enough to his tank, so we went in the bushes, in the hedgerow. I jumped in, I’ve got my arm around him, and they were still shelling. You’re praying that nothing hits you, but he got hit. And I didn’t know it. I had my arm around him. It’s fate, that’s all I can say it is. Because when I said, ‘Okay, Ed, everything’s okay, let’s get going,’ uh-uh. He was hurt.”

Ed was orderly, businesslike and matter-of-fact, all traits he picked up from Reverend Laine. But he was not without a sense of humor.

“If you want to get ahead in this man’s Army,” he wrote early in 1944 to his kid brother Elmer, who’d just been drafted, “you’ve got to be a screwup.” Elmer recalled he might have used a word other than “screwup.”

Elmer was in England waiting to go into combat with the 30th Infantry Division when he learned in a letter from his father that Ed was in a hospital nearby. He got permission to visit him and the two spent a weekend together.

As they walked around the hospital grounds, servicemen would salute Ed, who would salute back and mutter under his breath, “Same to you.”

“Why are you saying that?” Elmer asked.

“Because they’re thinking, ‘You no good SOB.’ ”

The day after the

barrage in which Ed was wounded, Goldstein was sent to the rear with

three drivers to pick up replacement tanks. He stopped at an aid

station to get the ringing in his ears checked out, and the medic

called

the

doctor over. The doctor told him his ear drums were perforated and

he’d have to be evacuated. Goldstein was the only person who knew the

way back to the outfit, and said he couldn’t be evacuated. The doctor

said he didn’t have a choice. Goldstein gave him that choice by

removing his .45 from its holster.

the

doctor over. The doctor told him his ear drums were perforated and

he’d have to be evacuated. Goldstein was the only person who knew the

way back to the outfit, and said he couldn’t be evacuated. The doctor

said he didn’t have a choice. Goldstein gave him that choice by

removing his .45 from its holster.

Ed was still in a hospital in England when he received a visit from Elmer, who was waiting to go into combat with the 30th Infantry Division. Ed told Elmer he still had 17 pieces of shrapnel in him, but that he was returning to the battalion and would have the shrapnel removed after the war. His and Goldstein’s reactions to their injuries demonstrate the kind of loyalty the 712th inspired, although similar devotion to a soldier’s unit existed almost everywhere in the Army.

Ed returned to the battalion in November, with plenty of war still ahead. In all, the 712th Tank Battalion spent 311 days in combat, most of them, according to its unit history, engaged with the enemy. However, the third platoon already had a new lieutenant and A Company was on its fourth company commander since Merrill was wounded on July 13. One of those company commanders was Capt. Ellsworth Howard, the company’s executive officer, who took over for Merrill and was wounded at Chambois during the closing of the Falaise Gap. The company still needed an executive officer, so Ed Forrest was given that relatively safe position. His duties included setting up headquarters and finding houses in which to billet the service troops.

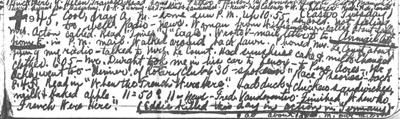

Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, was a “mild, sunny, beautiful day,” Laine wrote in his journal. The journal was actually a daybook, a large, leatherbound volume with 365 pages and seven lines for each of five years on a page. He noted that 25 people received Holy Communion, and that he had breakfast at 8:40 a.m. He wrote a V-mail letter to Ed and noted in parentheses that it was “No. 1097” that he had written since Ed went into the service. In the afternoon he listened to the New York Symphony performing Bach’s “Passion” on the radio. He had duck and champagne for dinner.

Three thousand miles away, the 712th Tank Battalion was moving steadily through Germany. On April 3rd, as it approached the Werra River, the battalion entered the village of Heimboldshausen. A group of SS soldiers were dug in on the far side of town, and the fighting troops were sent to deal with them. Ed went about the business of selecting a headquarters and houses for the service personnel.

The houses he chose were near a small depot where several rail cars were parked. On the far side of the depot was a large open field. In the distance there was a stand of pines atop a man-made mountain of slag from nearby potash mining operations.

Ed set up his headquarters in the basement of a house near the tracks. A disabled tank was parked outside, alongside a truck with 300 five-gallon jerry cans of gas. The truck had a ring-mounted .50-caliber machine gun. In a corner of the area between the houses and the depot, Ervin Ullrich, the A Company cook, began preparing a hot meal.

In Stockbridge, on the evening of April 3, Laine noted in his journal that he dined on “duck and chicken sandwiches” – leftovers, no doubt, from Easter dinner. He noted also that he finished reading “When the French Were Here,” a book by Nobel Prize winning historian Stephen Bonsal that tells of the role of France during the American Revolution. {The book tells how George Washington was unable to pay the troops, and the “ladies of Havana” raised $1 million in 1776 dollars, inscribing on their contribution “so the American mothers’ sons are not born as slaves.” In 2000, when the U.S. government allowed Elian Gonzalez to be returned to Cuba, commentators in Miami conjured up this episode and remarked: And this is how we repay the ladies of Havana for saving the American Revolution.”}

On April 4th, the morning in Stockbridge was cold and dark. Laine wrote both a V-mail and an airmail letter to Ed, then attended a monthly meeting of the library trustees. In the evening he listened to the news on the radio, and then to commentaries by Harry Marvell, Raymond Swing and H.V. Kaltenborn.

It was even colder on the 5th, but the sun came out at noon. There were snow flurries in the afternoon. He wrote a V-mail letter to Ed. Late at night he snacked on sunshine cake and a baked apple, a specialty of his housekeeper, Jessica French.

Friday was uneventful, but Saturday was a hectic day. While Laine was writing a letter to Ed, he “was interrupted by phone from New York from Gertrude Robinson Smith saying that her mother had died.” Stockbridge was a summer retreat of the wealthy, and Laine’s congregation was well-represented in the Social Register, with Merwins and Choates and Sedgwicks; the senior warden of the church was Rodney Procter, one of the founders of Procter & Gamble. (The junior warden was Edward L. Forrest.) Gertrude Robinson Smith was the philanthropist who raised most of the money for the cultural institution known as Tanglewood.

On Sunday, Laine had breakfast at 8:35. At 9:15 he went to the neighboring town of South Lee to perform a baptism. After services at St.. Paul’s he wrote a V-mail letter to Ed, noting parenthetically that it was No. 1106. And then a minor tragedy struck: His radio went on the fritz.

He phoned a repairman, who said he would have to take it home to work on it. Laine went to Ed’s study in the parish house to get Ed’s radio, and the handyman helped carry it back (radios were big and bulky in those days). He noted in his journal, probably somewhat wistfully, that it was the first time he’d been in Ed’s study in a year and a half.

In Heimboldshausen, several empty ore cars were parked at the railroad siding, along with a pair of fuel tanker cars that were empty and a boxcar filled with bags of black powder. Atop the gasoline truck parked outside the A Company headquarters, Pfc. Joseph Fetsch of Baltimore was oiling the ring-mounted machine gun. Earlier in the day a German plane was spotted and when he went to swing it around, it was rusted into place.

Ed was in the basement

of the house next to which the gasoline truck was parked, setting up

his headquarters. It was about 6 p.m. Suddenly, there was a shout:

“Plane!” A Messerschmitt 109 was flying low over the empty field

toward the village. Everybody with a weapon began shooting at it.

Fetsch swung the ringmount

around

to start firing. The next thing he remembers is waking up in a

hospital two days later.

around

to start firing. The next thing he remembers is waking up in a

hospital two days later.

On Tuesday, April 10, Laine received a pair of V-mail letters from Ed, one written March 26 and the other March 29. He performed the committal service for Mrs. Robinson Smith. On the 11th he wrote an airmail and a V-mail letter to Ed. His entry in the journal for April 12 contains the following underlined passage {5:50 – turned on Radio (WABC) – heard news of death of Pres. Roosevelt.” That evening, he noted, all regular radio programs were replaced by news about Roosevelt.

Saturday, April 14, brought “terrible news of the death of Tommy Burt on the Western Front.” Burt was a local boy serving in the Army. (His brother, Jimmy Burt, serving with the 14th Armored Division, would be awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor.) At 4 p.m. Laine performed a Memorial Service for President Roosevelt, and noted that there was a large congregation. He wrote an airmail letter to Ed and put some clippings in it. He mailed the letter on the way to South Lee to call on Tommy Burt’s family, noting that there was “great sorrow” in the household.

On April 15, Laine woke up at 7:40 a.m. He listened to the news on the radio, and heard that the 90th Infantry Division, which he knew was Ed’s, was “near “Czecho-Slovakia – 13 miles.” In his sermon that morning he spoke of Tommy Burt. Then he wrote a V-mail letter to Ed and noted that it was No. 1115. That afternoon he dozed in the Morris chair in his study. The repairman came with his radio, set it up, and helped the reverend put Ed’s radio back in his study.

Pfc. Orville Moody of Asheville, North Carolina, had traded places with Joe Fetsch on the morning of April 3rd. Otherwise, Fetsch would have been driving supplies to the tanks on the line, and Moody would have been back in the village. Moody heard the explosion and saw the huge plume of smoke rising from Heimboldshausen. He turned his truck around, stepped on the gas and was one of the first to arrive on the scene. He remembers seeing the wreckage of the ME-109 which, flying low, was caught in the explosion and crashed into a barn in the village adjacent to Heimboldshausen. All that was left of the pilot was his boots, which were still smoking.

Some of the battalion’s veterans recall the explosion as having been caused by the carload of black powder. In actuality it was the two empty fuel tanker cars, which were filled with fumes. Either bullets from the plane or those being fired at it struck the cars and set off the explosion. Fetsch, standing atop a truck carrying jerry cans filled with 1,500 gallons of high-octane gasoline, survived because the concussion from the blast kept the gasoline from catching fire. Pieces of the tanker cars were found in a village two miles away. The explosion blew the roofs off 30 houses and razed the four houses closest to the tracks. Of the 32 members of the tank battalion who were in the village, only three were not injured. Five members of the battalion, including the cook, Ervin Ullrich, and Lieutenant Edward L. Forrest, who was in his basement headquarters when the house collapsed, were killed.

The morning of April 16, 1945, was dark and drizzly, Reverend Laine noted in his journal. At 1 p.m., he listened on the radio to President Harry Truman’s speech to Congress. He wrote a V-mail letter to Ed, had a meeting about the church water bill, and spoke with a parishioner about the baptism of her daughter. He wrote a note of thanks to Gertrude Robinson Smith, who likely made a substantial contribution to the church in her mother’s name. In the evening, while he was reading the New York Times, he received a phone call from the Great Barrington telegraph office.

Some time later, when he

was able to get more details, he went back in his journal and placed a

thick black

cross

in front of the entry for April 3, 1945. He then added a footnote:

“(Eddie killed this day in action in Germany) at about 12 p.m. our

time.”

cross

in front of the entry for April 3, 1945. He then added a footnote:

“(Eddie killed this day in action in Germany) at about 12 p.m. our

time.”

Norman Rockwell married a parishioner of St. Paul’s, Molly Punderson, and moved to Stockbridge in 1950. Ann Braman, the wife of Ed’s buddy Dave, posed for Rockwell as the Schoolteacher in the painting of the same name. Dave’s father, who owned a general store on Main Street, posed as the Village Clerk in “The Marriage License.” Dot Cooney, who dated Ed before the war, can be seen bicycling down Main Street in a video shown at the Rockwell Museum. Ed Forrest never got the chance to pose for Rockwell, or to become the prominent citizen of Stockbridge Reverend Laine hoped he would someday be.

Reverend Laine never got over Ed’s death. Later in 1945 he burned all of the letters he received from Ed. He left Stockbridge around 1950 and took a job as the chaplain at the Manlius Military Academy outside Syracuse, N.Y. He stayed there until he retired, and died there in 1969 at the age of 80.

Dorothy Cooney, who knew both Ed and Reverend Laine, says the journal, crammed with information as it is, doesn’t do justice to the minister’s eloquence. A better example might be the inscription in “England to America,” which Laine passed on to Ed’s friend Dave Braman, who was a fighter pilot during the war, in June of 1946.

On the inside cover is a sticker saying “Library of Edward L. Forrest.” On the title page, Laine wrote: “Dear Dave, This classic little story of the First War of 1917-1918 was a great favorite with Eddie. I gave it to him in 1929, and he read it many times. You and I can appreciate the truth, the grace and the poignancy of this narrative, since like Chev Sherwood [the captain in the story], Eddie passed over, fighting gallantly for his country. Little did he think as he read it, that the years to come would call him to the same manly sacrifice. You were his beloved friend, keep this cherished book of his, in proud remembrance.”